As EU Council President Charles Michel prepares to bring together the leaders of Armenia and Azerbaijan in Brussels, there are serious concerns that the humanitarian emergency in Nagorno-Karabakh may be a prelude to wider escalation in the southern Caucasus. For more than four months, the enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh has been under a blockade causing a dire humanitarian emergency, with vital supplies of food and medicine dwindling rapidly. The enclave’s disputed status is part of the wider conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, which has oscillated between hot wars and frozen conflict.

The last “hot” war happened as recently as 2020, when most of the world was preoccupied with the COVID-19 pandemic, which limited the political attention and bandwidth paid to it. In the space of a few weeks in 2020, some 7,000 people were killed, including by drones. (As the Ukraine war has highlighted the ways in which drones are changing the battlefield, it’s worth remembering these weapons have been tried out elsewhere first, from Syria and Libya to Azerbaijan and Armenia, and the Turkish-made Bayraktar drones that are celebrated in Ukraine are a source of anguish to Armenians).

Fighting was halted by an armistice agreement, which included the deployment of peacekeepers from Russia, which has traditionally had close relations with Armenia but has also more recently developed its ties with Azerbaijan. But the armistice, which made a commitment to the free and safe movement of people and goods, is no longer being fully respected. There is a risk that the festering conflict will escalate again, in part because of the disruptive international effects of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. As the Minsk Group of governments tasked by the OSCE with addressing the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh appears to be barely active, the EU role will be critical.

There is a risk that the festering conflict will escalate again, in part because of the disruptive international effects of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Jane Kinninmont

In February and March, ELN staff consulted network members of various nationalities to test out some possible humanitarian and diplomatic recommendations. Although the south Caucasus has not in general been a focus of ELN research, our network includes members from all of the countries affected, and several sources raised concerns that Europe should be paying more heed to early warning signs of conflict and displacement risks in the region. In particular, a number of people warned that the dire humanitarian conditions resulting from the ongoing blockade of the Lachin Corridor will eventually force the 120,000 Armenians of the enclave either to fight for their lives or flee to Armenia.

As indications of the risk, they pointed to recent statements by Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev, who has recently said that residents of Nagorno-Karabakh who are not willing to become citizens of Azerbaijan should leave. (The ethnic Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh want self-determination and fear that if they were forcibly integrated into Azerbaijan they would be an extremely oppressed minority given the long history of conflict and animosity between Armenia and Azerbaijan.) These statements have compounded concerns that the siege of Nagorno-Karabakh is a deliberate strategy to intimidate the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh and ultimately force them out. This would constitute mass displacement, in a politically fraught region that has a history of forced displacement. It would set back indefinitely the (already uneven) prospects for democratic governance, economic development, and human security in the region.

The geopolitical context for the blockade

Since 12 December 2022, Azerbaijani nationals have enforced a blockade on the only road between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, the 5 km Lachin Corridor. This has cut off vital supplies to the 120,000-strong population of ethnic Armenians in the enclave. Repeated interruptions of gas and electricity to Nagorno-Karabakh have compounded the emergency. A firefight in early March, which killed five people, was a reminder of the risks of escalation.

The people implementing the blockade claimed to be independent protestors but were widely seen as a proxy for the Azerbaijani government, and, indeed, they have duly paved the way for the overt involvement of the Azerbaijani authorities in the past few weeks. In late March, Azerbaijan’s defence ministry announced it had taken control of a dirt track that passed close to the Lachin corridor. This move prompted a rebuke by the Russian peacekeepers in the area, who noted that Azeri forces had crossed the agreed line of contact and should withdraw. Nonetheless, since then, the Azerbaijani foreign ministry has set up a checkpoint and says work has begun to “establish control” of the Lachin corridor.

The people implementing the blockade claimed to be independent protestors but were widely seen as a proxy for the Azerbaijani government, and, indeed, they have duly paved the way for the overt involvement of the Azerbaijani authorities in the past few weeks. Jane Kinninmont

In terms of reactions from governments, the U.K., U.S., France, Germany, Switzerland, Ireland, Norway, Lithuania, Netherlands, Vatican, Brazil, UNICEF, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, the European Parliament, the European Court of Human Rights and others have expressed concern about the humanitarian consequences of the blockade. Moreover, in a significant decision issued on 22 February 2023, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) has ordered Azerbaijan to “… take all measures at its disposal to ensure unimpeded movement of persons, vehicles and cargo along the Lachin Corridor in both directions.” [para. 62] However, little has been said by Russia, nor by another key regional player, Turkey.

The longstanding conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan has local roots, but wider international geopolitics are influencing local calculations, and have eroded the existing mechanisms for conflict resolution. For instance, in a recent brief for the Wilson Center, Lara Setrakian argues that the OSCE Minsk Group, set up in 1992 to help resolve the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and co-chaired by the US, Russia and France, fundamentally reflected the zeitgeist of the 1990s: “the new Russia working with leading countries of the West to solve problems in the former Soviet states”. Conversely, she argues, today “collaborative leadership is hard to imagine”. Instead, she calls for the US to push for a resolution at the UN Security Council calling on Azerbaijan to implement the ICJ resolution.

The longstanding conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan has local roots, but wider international geopolitics are influencing local calculations, and have eroded the existing mechanisms for conflict resolution. Jane Kinninmont

Some, like Russian journalist Kirill Krivosheev, writing for Carnegie Politika, have also argued that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has changed Russia’s priorities in the Caucasus. Specifically, it has weakened and distracted Russia from playing an effective peacekeeping role in Nagorno-Karabakh, while also making it more important for Russia to have good relations with Azerbaijan, and with Azerbaijan’s ally Turkey. These trends may have emboldened Baku to create new facts on the ground with the blockade. Meanwhile, from Azerbaijan’s point of view, there may be concerns about what it sees as growing Russian influence over Nagorno Karabakh, as is noted in this interview with longtime Caucasus conflict analyst Laurence Broers.

Some views from the Network

As with most long-running conflicts, there is a battle of narratives, and any description of the situation quickly runs into sensitivities over being perceived as pro-Armenian or pro-Azerbaijani. A group of scholars specialising in the region recently wrote that the study of its past and present has been hijacked by competing political narratives, shaped both by Soviet legacies and modern-day censorship, to the extent that history has become weaponised rather than providing lessons for pathways to peace. This article – unusually and impressively – was published in parallel by Armenian and Azerbaijani institutions, and called on academics from Armenia and Azerbaijan to hold their exchanges within academic parameters rather than defenders of national positions.

I saw this in microcosm when the ELN tested out various forms of language with our members for a possible public statement and considered how to construct a sense of shared interest without descending into platitudes. For instance, we discussed the merits of a public call for the rights of the ethnic Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh to be respected, given the specific threat against them, versus a wide-ranging call for respect for the rights of all ethnic groups in the region. In one memorable phrase, one said “we cannot say this yoghurt is not white just to please the colourblind”.

In terms of the prospects for diplomacy, it was noted by some members that there had been some limited direct contacts between the government of Azerbaijan and the de facto authorities in Nagorno-Karabakh, which some saw as a positive development that should be left to proceed without public calls for specific steps. By contrast, others cited reports that the contacts had largely reiterated Aliyev’s public line: that the inhabitants of the enclave should either become Azerbaijani citizens, or leave. Moreover, Azerbaijan has traditionally favoured the idea of direct talks with the Nagorno-Karabakh authorities without international mediation or facilitation, to underscore its position that Nagorno-Karabakh is an international issue and that the enclave should be integrated into Azerbaijan.

As with most long-running conflicts, there is a battle of narratives, and any description of the situation quickly runs into sensitivities over being perceived as pro-Armenian or pro-Azerbaijani. Jane Kinninmont

In these discussions with members of the ELN, some had the view that the Minsk group has become so irrelevant that even calling for it to act could be seen as an indication of naivete and distance from the conflict. Some were more hopeful about the growing role of the EU, which has been mediating between Baku and Yerevan, with active support from the US and France; Germany’s Chancellor will also join the French President for a meeting with President Aliyev and Armenia’s President Vahagn Khachaturyan on the sidelines of the June meeting of the European Political Community. It was also said that the recently established EU monitoring mission on the Armenian side of the Armenia-Azerbaijan border has helped to ensure that the border has been quiet and without incidents.

The potential for improving relations between Armenia and Turkey, which have been quietly developing a détente, was also seen as beneficial for regional peace and security (the subject of a previous ELN commentary and consultation). This might pick up pace after the upcoming Turkish election. At the same time, from slightly further afield, the rising tensions between Iran and Israel (over Iran’s nuclear programme and regional policies) could also potentially have negative spillover effects into the Caucasus. The south Caucasus has been mentioned repeatedly in separate ELN meetings about Iran and the risks if the JCPOA cannot be revived. Discussants have noted that as both Iran and Russia have a growing, shared interest in bilateral trade to mitigate the effects of international sanctions on their economy, land routes between them are becoming more significant and more contested. As Azerbaijan enjoys close relations with Israel and Armenia with Iran, there are a number of ways in which Iran-Israel tensions can affect them.

Ultimately, one area of common ground was the acknowledgement that there is both an urgent need to address the humanitarian situation, and to re-energise and revive diplomacy to address the broader conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, already festering for too long. Even if the Minsk Group countries can no longer work effectively together, it may be worth exploring whether Russia and the EU at least share a common interest in preventing a renewed outbreak of hostilities between Azerbaijan and Armenia or a further mass displacement in the region. Conversely, given that the conflict to date has already left a bitter and divisive legacy, any mass displacement would surely entrench enmities for the longer term, with negative consequences for the region.

The opinions articulated above represent the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Leadership Network or all of its members. The ELN’s aim is to encourage debates that will help develop Europe’s capacity to address the pressing foreign, defence, and security policy challenges of our time.

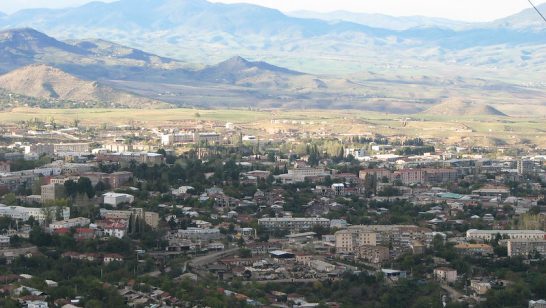

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons / Mahammad Turkman