With the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, US and Western European pundits predicted devastating and crippling cyber effects predicating kinetic warfare. However, over the past weeks, numerous Russian actions in cyberspace have largely flown beneath the radar due to actions by the cyber-security industry, or so-called “patriotic hackers”, who have taken it upon themselves to counter Russian cyber aggression and attack Russian cyber infrastructure. In light of developments such as these, the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) should consider and create policy for collective cyber defence, and potentially offense, under Article 5 of the NATO Charter.

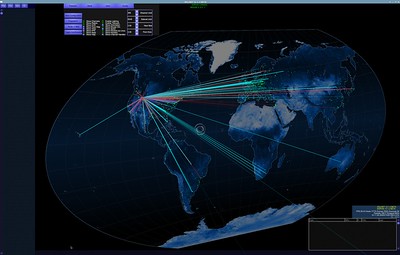

Cyberspace has proliferated across the globe, particularly in critical infrastructure, as technology has eclipsed traditional definitions of computing. Non-traditional computers reside in pockets, are able to make phone calls, and, increasingly, take high-resolution photographs. These non-traditional computers also maintain proper food temperatures in kitchens, give directions in cars, and track movement and health on people’s wrists. But more importantly, these non-traditional computers reside in critical infrastructure centres displaying data for operators in the form of large screen monitors on walls, showing the physical environment through closed circuit television cameras. Many of these devices, which frequently lack anti-virus protection and utilise vulnerable protocols, exist within critical infrastructure, either natively or brought into these environments by employees. Electrical power generation and distribution, telecommunications, finance, and water treatment and distribution are some examples of critical infrastructure that are managed by computer-controlled systems. Compounding the problem, the internet does not abide by national boundaries, making forensic investigation and attribution difficult. Critical infrastructure sectors rely heavily on automation, and thus online control, as described in the U.S. National Strategy for Maritime Cybersecurity.

Recent state activities demonstrate how cyberoperations can have physical consequences. In the summer of 2020, Iranian hacking of Israeli water treatment facilities came close to over-chloritizing the water, changing faucets into poison dispensers. More recently, in February 2022, in an attempt to cut communications within Ukraine, Russian cyberattacks on Viasat satellite networks disrupted German windmill electricity generation and distribution. Additionally, Russia has in the past—and continues in the current war as recently as April 2022—to target electrical power generation and distribution systems with cyber effects and to harm Ukrainian civilian and military infrastructure. As the above examples show, cyber attacks are not limited to online locations but their impact can be felt in the physical world. As a result, NATO must prepare for these activities to grow and expand.

Following the shortcomings of the 2015 United Nations Group of Governmental Experts report on information and telecommunications in the context of national security, a lack of consensus continues to exist on the severity of cyberspace operations targeting critical infrastructure requiring collective and even national responses. Individual nations constructed individual criteria and response actions, utilising diplomacy, information, military, or economic action. They largely did so alone or in combination with other states. NATO, however, did not formulate a coherent analogous response and as a result, lacks publicly acknowledged policy addressing cyberspace activities that would constitute a necessary collective response under Article 5. In order for NATO to maintain its relevance in the present moment and sustain it through the coming years, this paradigm must change.

NATO must adjust its thinking regarding methods of warfare as cyberspace operations—both destructive attacks and disinformation—continue to grow in complexity and in certain areas even replace traditional kinetic operations. To fulfill this role in kinetic as well as non-kinetic realms, NATO must be prepared for hybrid forms of warfare and present slated to join the alliance a cohesive and tailored response to transgressions. This is increasingly important as Russia continues to threaten potential future NATO members such as Finland and Sweden, who are slated to join the alliance in the coming months. Russia has overtly stated that the invasion of Ukraine was, in part, a response to NATO’s eastward expansion. Although Russia has deemed NATO expansion into former Soviet states to be problematic since the collapse of the USSR, recently, Moscow has also begun to denounce potential expansion beyond its perceived immediate sphere of influence. For example, on April 14, 2022, Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergei Lavrov cautioned that the inclusion of Finland and Sweden into the military alliance would have dire consequences, including Russia reinforcing nuclear weapons in the Baltic Sea region.

Considering the increased emphasis and relevance of the transatlantic alliance leading up to and during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it is imperative for the organisation’s member states to identify and agree upon more pronounced “triggers” or “red lines” that determine what constitutes a sufficiently egregious action in cyberspace for Article 5 to be discussed, and if need be, potentially invoked. Furthermore, in enhancing its preparedness in cyberspace, specific policies must be crafted that delineate synchronised actions taken collectively by members to prevent Russian malign activities in the cyber domain under Article 5 to allow for a rapid and coordinated response. The dominance of the US, the UK, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, known in government as the FVEY, or Five-Eyes, highlights the urgent need for the alliance to develop policy addressing the collective defence of NATO members. Effective policy for NATO should address collective and coordinated cyberspace operations, both offensive and defensive. Currently, NATO, as a military institution, lacks “rules of engagement” for cyberspace and individual member states lack a standardised threshold or response guidance. Therefore, NATO must define the activities, “red lines”, and threshold incurring response, as well as what a coordinated kinetic/cyber response would entail. The interconnectedness of European critical infrastructure, as illuminated by the Russian ViaSat communications attack impacting German wind power generation and distribution, highlights the requirement for NATO to address cyberspace as the critical domain it is. As a result, we recommend:

- In the event of adversarial cyberspace actions warranting Article 5 action, the NATO Commander becomes the commander and coordinator for all cyberspace activities, both defensive and offensive, by NATO nations within the area of hostilities.

- NATO identifies, establishes, prioritises, and continually refines critical infrastructure and key resources within member nations, as well as criteria for what constitutes necessary action for collective responses.

- NATO identifies limits of activity, or “red lines” resulting in Article 5 response discussions.

- NATO members present the NATO Commander intelligence identifying indications, warnings, and attribution of cyberspace attacks, both for response action and, where applicable, public consumption.

- NATO members present legal constraints and capabilities of nations to the NATO commander allowing maximisation of nations’ capacity and capability.

NATO must recognise cyberspace for what it is—an interlocutor of networks and devices from control systems for critical infrastructure to seemingly anonymous devices operating in the background of our lives. This interconnectedness by an invisible thread of information, however, is the critical vulnerability in the stability of societies. NATO must plan to protect the infrastructure and key resources of member states as a unified effort, not a piecemeal operation undertaken by a few nations. In order to do this, NATO must identify and prioritise infrastructure for protection, as well as criteria and policy for action. Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine and the Kremlin’s increased aggression, not solely in kinetic but also in non-kinetic realms, is a stark reminder that the alternative to further delay of the inevitable recognition of cyberspace for what it is will, ultimately, prove to be all the more costly.

The opinions articulated above represent the views of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Leadership Network or any of its members. The ELN’s aim is to encourage debates that will help develop Europe’s capacity to address the pressing foreign, defence, and security policy challenges of our time.

Image: Wikimedia Commons, Ecole polytechnique