In the last few years, there has been a rise in interest around the Arctic. For geopolitical analysts, the focus is on its potential as the next theatre in great power competition between the United States, Russia, and China. They are concerned with perceived Russian militarization and increased Chinese economic interest in, for example, Greenland and Iceland. Energy policymakers, meanwhile, are thinking about the region’s potential to free Europe from energy dependence on Russia and China and are considering the role that new shipping lanes namely the Northern Sea Route and the Northwest Passage, might play in shortened trade routes. The Arctic offers up opportunities for energy security by lessening dependence on Russian oil and gas imports in the short term and renewable energy sources such as wind power in Arctic coastal areas, hydropower, and solar in the long term.

In April, the European Parliament released its latest Draft Report on the Arctic. In it – and in anticipation of the EU’s new Arctic Policy slated for release in 2021 – the EU proposes taking a middle road that acknowledges geopolitical competitive realities in the High North while also opening a pathway for cooperation on transnational issues that affect all Arctic stakeholders, such as climate change, pollution, and coming to agreements on key questions of fishing.

The EU proposes taking a middle road that acknowledges geopolitical competitive realities in the High North while also opening a pathway for cooperation on transnational issues that affect all Arctic stakeholders... Gabriella Gricius

Competition in the Arctic

Whether or not the Arctic has historically been a place of competition varies depending on who you ask. The common narrative goes that since the end of the Cold War, the Arctic has been a zone of peace and international cooperation. The creation of the Arctic Council in 1996, the Northern Forum in 1991, and other regional organisations all appear to support this view and have helped make cooperation possible. But despite the proliferation of institutions and the absence of actual conflict, the geopolitical factors that can lead to competition have not gone away.

Take US resistance to China’s presence in the Arctic. When China expressed interest in investing in Greenland’s infrastructure including an airport and port, for example, it resulted in the US announcing a $12.1 million USD aid package to Greenland to counter Chinese and Russian interests and then-President Trump even floated the idea of buying Greenland. With the unprecedented melting of sea ice in the Arctic, China – who calls itself a ‘near-Arctic state’ – has indicated economic interest both in cooperating with Russia to build infrastructure for the Northern Sea Route, as well as in investing in Greenland and Iceland.

Emerging access to the Arctic has also led to increased military activity in the region. When Russia reopened over 50 old Soviet bases, building the first nuclear-powered icebreaker, and heavily invested in Arctic-capable military forces, it is easy to see how Europe and its allies could buy into the competition narrative. These issues are not inconsequential concerns – they are very real geopolitical realities that Europe must address, but it is certainly not just Russia. Consider the increasing military flights and naval exercises across the Arctic by the United States, Canada, and European states. Norway also recently approved a new Air Station in the Arctic for new aircraft to be built with submarine-detection technology and torpedoes to eliminate hostile submarines. The need for increased awareness of the Arctic as it opens is also evident in the United States, where all of the branches of its Armed Forces have produced Arctic strategies for the first time.

Cooperation in the High North

The focus of the Draft Report is on the possibilities for cooperation; the Arctic does not have to fall into old patterns of being thought of as a place of competition. Instead, it can be a place for cooperation on areas of shared concern, such as climate change, pollution, and agreements on fisheries. Most interesting is the Draft Report’s acknowledgement that understanding the environmental situation in the Arctic also requires knowing and considering questions of geopolitics and security.

Most interesting is the Draft Report’s acknowledgement that understanding the environmental situation in the Arctic also requires knowing and considering questions of geopolitics and security. Gabriella Gricius

Underlying all EU policy on the Arctic are its three founding pillars: climate change, sustainable development, and international cooperation. Any European policy that relies on these pillars must therefore start with cooperation rather than competition. There is no shortage of policy areas that would not only benefit from but also require cooperation on an international level. For example, the Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement, which entered into force in June, represents a cooperative way to approach unregulated commercial fishing in the Central Arctic Ocean, which includes Canada, China, Denmark, the EU, Iceland, Japan, Norway, Russia, South Korea, and the United States. Arctic states also agreed to cooperate on various agreements, including the Agreement on Cooperation in Marine Oil Pollution Preparedness and Response in the Arctic. Policies and cooperation that look at these transnational issues will continue to emerge as the impacts of climate change grow ever prevalent, particularly in the Arctic.

Consider the recent IPCC report that so clearly spelt out the consequences of continued global warming, not only globally but also in the Arctic. Russia and the West have an opportunity to address this global human security concern, whether that means creating sustainable fisheries management, protecting Indigenous cultures and practices, oil pollution and preparedness, or adopting greener policies for the Arctic more broadly.

Taking an approach that prioritises cooperation does not mean throwing away geopolitical realities but requires taking seriously opportunities for collaboration. It is easy to fall into the competition narrative trap, but the Arctic environment and relations between Russia and the West will be better off by resisting that temptation and instead prioritising cooperation on addressing transnational threats that affect us all.

The opinions articulated above represent the views of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Leadership Network or any of its members. The ELN’s aim is to encourage debates that will help develop Europe’s capacity to address the pressing foreign, defence, and security policy challenges of our time.

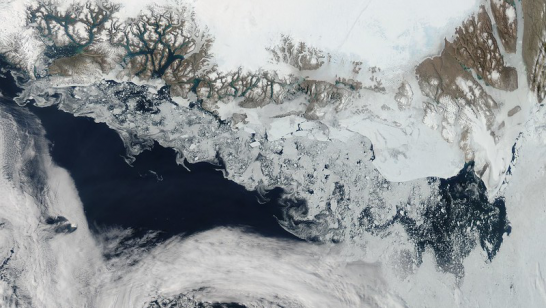

Image: Wikimedia