Three ‘frozen conflicts’ areas in the South Caucasus – in Nagorno Karabakh (NK), Abkhazia and South Ossetia – are situated near Turkey’s north-eastern border. Another conflict to its north, in Ukraine, typified by Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the recent Minsk 2 Agreement, seems, at best, being presently transformed into another ‘frozen’ dispute.

There are several prominent, and perhaps valid, reasons why old and new ‘frozen conflicts’ are of great importance for Turkey, and why Turkey has come to assume a position that simultaneously reflects a balanced overall policy and selective engagement approach. It is only these mixed policy approaches that will help first to reduce the deepening of, and then perhaps to outright resolve, the ‘frozen conflicts’ in the South Caucasus and the Ukrainian crisis.

A Balanced Overall Policy

Turkey has always favoured the principles of territorial integrity and self-determination as outlined in international law when it comes to the ‘frozen conflicts’ to its north, including Ukraine. Turkey is also well aware of the fact that these ethno-territorial disputes have never been simple disputes over land among dominant national and minority groups in the particular countries where they take place. They are also very much integral components of the geopolitical visions of great international and regional powers. In this sense, the Abkhazia conflict in Georgia and NK in Azerbaijan cannot simply be considered with regard to the legitimate demands of the Abkhaz and Armenian minorities in Georgia and Azerbaijan respectively, but must be examined by paying close attention to what Russia has envisaged and acted to create with the ‘near abroad’ policy it has followed since the early 1990s.

A long-time ally of the western security system, and proponent of the rule of international law, Turkey has supported the same approach that its western allies and Russia have adopted towards ‘frozen conflicts’, both within the OSCE as well as in other international mechanisms. Turkey has advocated the maintenance of the territorial integrity of Georgia, Azerbaijan and Moldova, while also urging that not all doors should be closed to the ethnic minorities that find themselves in conflict with their parent state. In the same vein, Turkey has continued to defend its pursuit of maintaining dialogue and developing relations with Russia, which, not just under Putin, has never shied away from demonstrating its reactions to the imagined security and geopolitical vacuum that the western powers have supposedly tried to fill in the post-Soviet area. To better illustrate this point, Turkey has developed its relations with Russia similar to the way that Germany and France developed their own relations with the country under Yeltsin, and later under Putin. On the regional level, despite the complaints uttered by the Georgian government, Turkey and the EU have tried to find ways to develop constructive and beneficial trade relations with Abkhazia after it was recognized as a de facto independent state by Russia in August 2008 after the Russo-Georgian War. Among other reasons for this course of action, they wanted to reduce Abkhazia’s dependence on Russia, both economically and politically.

The Selective Nature of Turkish policy

Turkey seems to have also assumed a selective approach towards these ‘frozen conflicts’. Ankara appears to take the side of certain parties involved in the ‘frozen conflicts’ to its north. Turkey’s support of Crimean Tatars in Ukraine, the permission it has given to its private sector to engage in trade with Abkhazia and its support of Azerbaijan over the NK issue may all be seen as the efforts of Turkey to promote its regional and international geopolitical interests. Indeed, such selective and tendentious positions are much more related to Turkey’s own internal and external security, as well as to its legitimate social and economic interests in its immediate neighbourhood, than to its pure geopolitical ambitions.

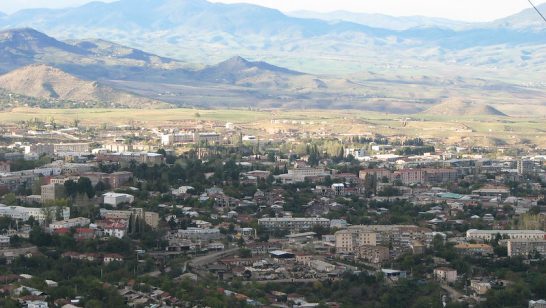

Turkey, for instance, promotes a peaceful resolution of the NK dispute between Azerbaijan and Armenia. Yet, in doing so, it has kept its border with Armenia closed and has not established diplomatic relations with Yerevan. Certainly, there are several reasons why Turkey acts in this way, or put differently, in support of Azerbaijan. Firstly, Turkey closed its border with Armenia in 1993 when Armenian military forces, in defiance of the UN Security Council (UNSC) resolutions, expanded their occupation of Azerbaijani territories. Secondly, Armenian military manoeuvres adjacent to the Azerbaijani region of Nakhichevan, which borders Turkey, threatened the security of Turkey itself. Thirdly, the Turkish public is very sensitive to the NK issue as it is characterized by the Armenian occupation of 20 percent of Azerbaijani territory and has resulted in tens of thousands of displaced Azerbaijanis who have the same ethno-cultural identity as the Turks. Fourthly, Turkey and Armenia share a long and problematic history that spans all the way back to the tragedy experienced by Ottoman Armenians in 1915. All this suggests that the ‘frozen conflict’ of NK is as much related to Turkey’s security as it is to Azerbaijan’s.

In short, Turkey sees all the ‘frozen conflicts’ in the South Caucasus as part of a particular regional security complex which should be considered collectively. Even though they have remained unfulfilled, Turkey’s efforts to form a Caucasian Stability and Cooperation Platform just after the Russo-Georgian War in August 2008, as well as its drive to push forward the Turkish-Armenian Protocols in 2009, have exhibited the objective to resolve these ‘frozen conflicts’ by developing complex economic and social interdependencies between all the regional actors involved.

What about the Ukrainian Crisis?

Indeed, Turkey sees the Ukraine crisis in general and the Crimea issue in particular through the same perspective. Turkey is very sensitive towards these disputes because they directly influence its own domestic stability and regional security. There are now more Tatar people in Turkey than there are in Crimea, just as there are three times more ethnic Abkhaz living in Turkey than in Abkhazia itself. Therefore, Turkey cannot turn a blind eye to the concerns of the Tatar people in Crimea.

Concerning regional security, Turkey is the central actor in maintaining peace and security in the Black Sea. The Montreux Convention of 1936 that regulates the passage of war and trade ships through the Turkish straights in times of war and peace is the key instrument in the region in that respect. Any incident that would question and damage the applicability of the Convention, especially in sensitive periods, could pose a great security risk for Turkey. Only an international legal obligation, imposed by the UNSC, and/or a unanimous decision of NATO, would impel Turkey to act. Any other unilateral action would be a dangerous undertaking that would drastically worsen the security situation in Ukraine and the Black Sea region.

Therefore, from the Turkish viewpoint, in order avoid turning the already difficult security situation into a nightmare, it is better to concentrate on the positive outcomes and possible benefits that all sides have so far garnered, and have yet to garner, from cooperation and dialogue, no matter how hard this may be.

The opinions articulated above represent the views of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Leadership Network or any of its members. The ELN’s aim is to encourage debates that will help develop Europe’s capacity to address the pressing foreign, defence, and security challenges of our time.