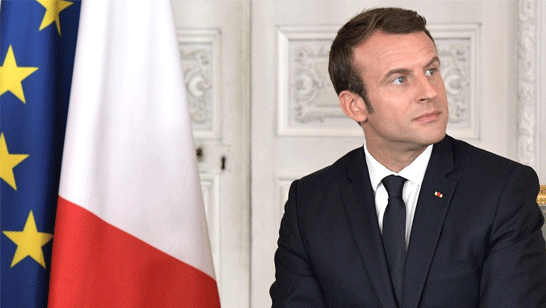

President Macron’s speech at the Ecole de Guerre last month, contemplating the possible role of French nuclear deterrence in the context of European security and defence, did not receive the attention one would have expected for such a significant announcement. The outbreak of the coronavirus is not the only reason for this.

Macron’s thoughts have been expressed by several French Presidents in the past. In the 1950s, France shared the idea of a European military nuclear program with the defence ministers of Germany and Italy, only for General De Gaulle later to abandon the initiative as he wanted an all-French bomb.

However, the idea did not die out as other countries also hinted at such a possibility. In 1968, for example, US Secretary of State Dean Rusk indicated that the NPT (which was not yet in force at the time) would not prevent a possible new European federal state from inheriting the nuclear status of a European country. Furthermore, when Italy signed the NPT Treaty, it evoked a “European clause” which implicitly included such an option in the context of “progress towards unity with a view to the creation of a European entity”. Germany too developed similar arguments. But these precedents never led to concrete results: western European defence, through NATO, remained anchored to the US nuclear deterrence.

This time, however, President Macron did not limit himself to evoking an abstract hypothesis but also made operational suggestions. He began with the premise that an authentically European element is already intrinsic in French nuclear forces since the vital interests of France now have a European dimension. The time would, therefore, be ripe for developing – with the European partners that are ready to do so – a strategic dialogue on the “role played by France’s nuclear deterrence in our collective security”. Those countries could be associated with “the exercises of French deterrence forces”. “This strategic dialogue and these exchanges,” President Macron argued, “will naturally contribute to developing a true strategic culture among Europeans.”

Macron is well aware that his room for manoeuvre is limited because decisions on EU foreign and security issues are taken with the consensus of all member states. On nuclear issues, the EU has always been divided between nuclear and non-nuclear weapon members, as well as between EU NATO and non-NATO members (some of the latter are neutral). To reassure EU NATO members, Macron specified that both NATO and the European Union must remain the pillars of European collective security. To encourage the EU non-NATO members, he underlined that his project would not need the involvement of all EU countries (such an arrangement is envisioned in article 42.6 of the 2007 Lisbon Treaty).

Despite its operational tone, President Macron’s message was mainly meant, like those of his predecessors, for his military audience and was embedded in a long speech on French defence strategy. There is no evidence, so far, of a formal French proposal submitted through the EU framework and this is probably one of the reasons why other EU members have reacted very prudently (if at all) to the French declaration. Whilst Johann Wadephul, a senior member of the CDU party in the German Bundestag, has welcomed the French proposal, suggesting that the Republic’s weapons are placed under NATO and EU command, his voice is at the moment quite isolated.

More than the suggestion itself, what distinguishes Macron’s announcement is the changed political context. It is probably not a coincidence that Macron spoke only a few days after the formalisation of Brexit, following which Paris became the EU’s only nuclear weapons power and its only permanent member in the UN Security Council. Macron also mentioned additional game-changers such as “the multilateralism crisis and the regression of law in the face of power balances”, as well as the trauma for Europe of the US and Russian withdrawal from the INF Treaty. The choice to sink the INF Treaty, unlike the decision in 1979 to negotiate it, was taken without active European involvement.

The future of Macron’s initiative will depend very much on the long-term evolution of transatlantic relations. There is a growing divergence between Europe and the present US administration, not only on values such as multilateralism, respect for the international order and universalisation of the arms control treaties, but also on planetary issues such as climate change. This trend coincides with a growing Russian political and military assertiveness both in Europe and the Mediterranean. Although the US presidential election in November might be a turning point, a transition to a French/European nuclear deterrent would probably be a bite too big to digest at this stage. What is more feasible after Brexit – as also mentioned in President Macron’s speech – is for Europe to become “more credible and effective in NATO” which means, among other things, acting and speaking with a united voice in the framework of the Alliance.

The opinions articulated above represent the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Leadership Network (ELN) or any of the ELN’s members. The ELN aims to encourage debates that will help develop Europe’s capacity to address pressing foreign, defence, and security challenges.

Image: Flickr, francediplomatie