In anticipation of increased sea traffic in the Arctic Ocean and its peripheral seas, Russia has bolstered its Arctic military presence in recent years. It has reopened abandoned Soviet-era military installations, invested in the construction of new military bases and icebreakers, increased troop presence and Arctic military drills, and established advanced radar stations. Such actions have triggered discussions about Russian intentions in the Arctic, often described as revisionist and aggressive. How concerned should the West be?

Any military build-up is generally not an end goal in itself but a manifestation of national interests and priorities. With this in mind, Russia’s military build-up in the Arctic can be analysed against three priorities pursued by Moscow. First, to ensure perimeter defence of the Kola Peninsula and the survivability of second-strike nuclear assets. Second, to protect Russia’s commercial interests in its Arctic zone. And third, to address socio-economic and demographic challenges facing its polar regions. In examining these in turn, it is clear there is much more to Russia’s military build-up in the Arctic than mere muscle-flexing.

Protection of sea-based nuclear assets

From a military strategic perspective, Moscow regards Murmansk, the Barents Sea and adjacent Arctic waters as vital for maintaining nuclear deterrence and the defence of Russia. During the Soviet era, Moscow assigned particular importance to intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). Following the degradation of Russian military capabilities in the 1990s, however, sea-based nuclear assets became Russia’s main instrument of deterrence and the backbone of the country’s security.

In contrast to the US Navy, whose nuclear submarines sailed out into the deep oceans as “lone, stealthy combatants”, Russia opted for developing protected bastions – or sanctuaries – from where its submarines could operate near or under the ice cap and be protected by air and naval forces from nearby bases. The main task of the Northern Fleet, which accounts for about two-thirds of Russian naval power, was to protect and ensure the survival of the strategic sea-based nuclear assets. The fact that the Northern Fleet received funding even during the economic crisis of the 1990s reflects the importance accorded to the Northern Strategic Bastion in Russian military thinking. With this in mind, Russia’s efforts to modernise and expand its Northern Fleet in recent years can be interpreted as an effort to bolster deterrence against the West.

Protection of Russia’s economic interests

There is an important economic aspect to Russian Arctic activities. The 2008 strategic document on the Principles of the State Policy of the Russian Federation in the Arctic to 2020 and beyond envisages the “use of the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation as a strategic resource base”. Although estimates vary, Russia derives approximately 20% of its GDP and 30% of its exports from the Arctic. According to the US Geological Survey assessment, the Arctic is estimated to hold 13% of the world’s undiscovered oil, 30% of the world’s undiscovered natural gas, and 20% of the undiscovered natural gas liquids. In addition to hydrocarbons, the Russian Arctic contains significant mineral deposits, including rare metals, gold, platinum, and diamonds. Moreover, as more fish migrate northwards to escape warming waters, the Arctic Ocean increasingly presents a potentially lucrative fishing opportunity.

Developing the Northern Sea Route, and ensuring its safety and commercial feasibility, is crucial for Russia to reap these benefits. As a rule, if shipping lanes are economically important, countries will want to safeguard them militarily. A parallel could be drawn with the Strait of Hormuz, where US military presence ensures a free and uninterrupted passage of trade and, as such, secures American economic interests as well as those of its European allies.

Social development of Russia’s polar regions

Finally, with its military build-up, Russia seeks to address particular socio-economic and demographic challenges. As Wilson Center’s Global Fellow Stacy Closson points out, the social welfare function of Russia’s military build-up is often overlooked. Russia is home to about two-thirds (or 2.5 million) of all people who reside above the Polar Circle. Since 2000, the country’s Arctic population has shrunk by around 15%. Due to large amounts of out-migration, all of Russia’s polar regions are projected to experience continued demographic decline in the decades to come – with the exception of Nenets and Yamalo-Nenets autonomous districts, whose growth in oil and gas production continues to attract new residents.

In many countries, military installations come with federal funds that benefit local communities both directly – through infrastructure and community services – and indirectly, by providing employment and training opportunities, among other factors. In Germany, entire villages depend on the US military presence. The US Army and Air Force also provide a considerable economic boost to places like Fairbanks, Alaska.

This pattern is widespread in Russia too, where the military is considered the backbone of Arctic development. For years, as Russia has increased its military budget, social spending has declined. Many in the defence establishment have long argued that the increase in military spending is justified not only for national defence but also as a way to solve domestic economic problems, generate growth, and improve the quality of life of Russian citizens. Given the opaque nature of Russian defence spending in recent years, analysts in both Russia and the West have been speculating about the exact nature of the relationship between Russian military expenditures and socio-economic development. Although the exact figure is unknown, Closson outlines the possibility that a portion of the federal funds budgeted for military installations in the Arctic is going towards regional budgets, subsidising local towns and cities.

It is evident from the newly published Arctic Strategy that Russia considers the biggest challenges to its Arctic development to be domestic, rather than foreign. In this light, one of the main priorities up to 2035 will be to improve the livelihood of Russian Arctic residents. The strategy includes incentives to grow the Arctic population, by encouraging Russians to relocate to the Far North. Building sustainable communities alongside military outposts and supplementing regional budgets with military presence seems to be the likely way forward. Relocation of military personnel together with their families constitutes another means to repopulate the region.

Demonstration of world-class military capabilities

A fourth objective could be added, namely a credible showcase of Russia’s military might. As Dr Marc Lanteigne, Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Tromsø points out, classical international security theory distinguishes between offensive, defensive and ‘swaggering’ actions. ‘Swaggering’ is a term used to describe a display of military materiel for the purpose of enhancing domestic and international image and prestige rather than for a specific strategic aim.

Russia clearly seeks to demonstrate that it possesses world-class military capabilities. As of late, however, the country has endured a number of setbacks in its efforts to update the Northern Fleet. The situation in Russian ship-building and ship repair sector is particularly dire. The only aircraft carrier in Russia’s Navy, the Admiral Kuznetsov, suffered several incidents, including fire and dry-dock sinking during its refit program, resulting in additional delays and cost overruns. Russia’s new nuclear-powered ice-breaker Arktika experienced a motor breakdown during its first sea trials in the Baltic Sea in February this year. In 2019, a fire broke out on the special-purpose nuclear-powered submarine Losharik – dubbed a “jewel of the Russian submarine fleet” – killing 14 sailors. Despite all the hype, Russia’s nuclear-powered “Skyfall” missile, capable of flying at hypersonic speeds, appeared to have failed its flight test in August last year. In fact, there is a lot of scepticism as to whether nuclear-powered missiles will ever see the light of day. The question that remains to be asked is how credible are Russian Arctic capabilities and new weapon systems tested in the region?

Rather than mere muscle-flexing, the drivers behind Russia’s military build-up in the Arctic are multiple and diverse. The domestic drivers are often overlooked and deserve further attention. As well as defending its military and economic interests, Russia is equally concerned about the socio-economic and demographic challenges facing its polar regions, which the increased military presence can help address.

This commentary was prepared (in part) under a fellowship from the Kennan Institute of The Wilson Center, Washington, D.C. The opinions articulated above represent the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Wilson Center, the European Leadership Network or any of its members. The ELN’s aim is to encourage debates that will help develop Europe’s capacity to address the pressing foreign, defence, and security policy challenges of our time.

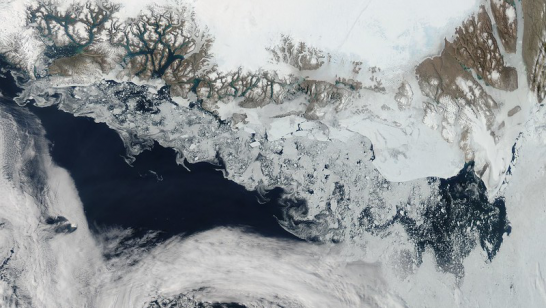

Image: Russian Arctic Trefoil military complex in Franz Joseph Land. Wikimedia Commons, Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation