Have you read an article about cyber this year? Perhaps it was about the taking down of Ukrainian government websites at the beginning of Russia’s invasion or the Conti ransomware attack on Costa Rica that led the government to declare a national emergency. Do you remember what image accompanied the article? And more importantly, do you think the image effectively communicated what the article was about?

Back in the mid-2010s, I worked at a think tank that was looking into new ways of warfare, such as the use of drones and cyber attacks. When trying to find images to accompany reports or articles on the topic of cyber, I encountered a problem. Online image searches pulled up image upon image that all looked the same: rows of 1’s and 0’s raining down in green and blue, a padlock, a close-up of a keyboard, or a hooded man in front of a computer. Fast forward to 2022, the ELN’s nuclear and new tech project is exploring the impact of new technologies on nuclear decision-making, and the same problem persists. While the importance of new technologies for conflict and international security has only grown in the past decade, the images used to represent them have remained static, and this hampers our ability to understand these issues and imagine the effects they may have on our future.

While the importance of new technologies for conflict and security has only grown in the past decade, the images used to represent them have remained static.

One new technology that is having a significant impact on international relations, and has received growing attention in the media, is cyber. From the 2007 ‘Nashi’ attack on the Estonian government, the 2010 ‘Stuxnet’ attack targeting Iran’s nuclear program, to Edward Snowdon’s NSA data heist in 2013 and Russia’s attack on the 2016 US presidential election, cyberspace has been described as “a global battlefield of the 21st century”. For the past few years, it has been high up on the US’s official list of national security threats, and tops the list of most European states, including the UK.

Despite its growing importance, cyber (like other new technologies) is complex and intangible and remains poorly understood by decision-makers and the general public, and by extension, photographers and photo editors. As a result, little attention has been given to the ways cyber is visualised, and image makers have little research to go on when they are considering making images on these topics. Similarly, journalists, campaigners, academics and policymakers have little evidence on which to base decisions they are having to make on a daily basis when selecting images. Based on interviews I conducted with cyber security experts from Europe, Russia, and the US, this piece explores why images matter to policy, what current cyber images are conveying and their impact, and how we might begin to communicate cyber issues more effectively.

The power and politics of images

W.J.T. Mitchell coined the “pictorial turn” in his 1994 book Picture Theory to characterise the nature of our world today. He argued that the wide consumption and increased attention to images in all spheres of life caused by media technologies has led to the power of the visual being greater than ever before as we increasingly perceive and remember key events through images. While Mitchell was referring to television, this became more pronounced with the rise of the Internet, which has transformed not only the speed at which images circulate and their reach but has also democratised images, doing away with the traditional gatekeepers of information. As a result, news images have become central to understanding and building the realities in which we live, made possible by the belief that photographs are truthful (“the camera never lies”).

Of course, we know this is not the case. Images are not “visual facts”, but rather they are reproductions whose meaning has been constructed by both the technology that has captured it and the particular perspective of the person behind the camera. They are also not neutral: their meaning is gained in relation to the society and culture they exist in, and because of this, they are inherently political. Colonial photographs from the 19th and early 20th centuries, for example, are understood very differently today than when they were made.

Images and new ways of warfare

In the early 2000s, images explicitly entered the security studies agenda, a recognition that visual representations are crucial to how security problems become known and debated. Esther Kersley

In the early 2000s, images explicitly entered the security studies agenda, a recognition that visual representations are crucial to how security problems become known and debated. According to Lene Hansen, this “visual turn” was, in part, a result of internal dynamics of academic debates (the wider “visual turn” that took place in the humanities) and developments in technology (the smartphone, cameraphone and social media that influenced the speed, reach, and production of images). It was also a result of important world events that involved or were shaped by images: In 2001, the overwhelmingly visual coverage in the world’s media of 9/11 meant images played an integral part in providing the attacks with a particular shape and status; in 2004, large number of photos released of torture and abuse by American military personnel from Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq had an independent impact on the scandal receiving global attention (textual accounts of what happened at the prison that appeared before the photos had generated little discussion); and in the 2015 Charlie Hebdo attacks, it was images (the Danish Muhammed Cartoons that the attackers sought to destroy and punish) that caused the event. Without the images – their production, circulation, and what they “say” – there would have been no event.

But something else was also happening in security studies at this time. Something that didn’t involve images and wasn’t visible, but was largely invisible. In 2013, Professor Paul Rogers wrote a paper for RUSI stating that “The dominant trend in international security over the past decade has been a move towards ‘remote control”. This describes the shift from engaging large military forces to conducting warfare indirectly or at a distance. It includes new technologies – such as armed drones and cyber activities, as well as new methods of warfare, for example, the increased use of special forces and private military companies. Almost a decade on from when Rogers wrote this, other emerging and disruptive technologies (EDTs), such as AI, machine learning, deep fakes and quantum technology, are playing an increasing role in conflict. These are both less visible and less tangible than, for example, soldiers and conventional weapons.

What happens to political phenomena that are hard to visualise? This is a challenge for today’s image makers when attempting to communicate contemporary threats, such as the climate crisis and new technologies. Esther Kersley

If politics and society are shaped both by what is made visible and what is left invisible, what happens to people, issues, and phenomena that we do not see or that there is an absence of images of? And what happens to political phenomena that are hard to visualise? This is a challenge for today’s image makers when attempting to communicate contemporary threats, such as the climate crisis and new technologies. When it comes to documenting new types of warfare, there have been attempts by some photographers to address this (for example, Simon Norfolk, Lisa Barnard, and Trevor Paglan), but these examples remain sparse and are situated in the “art” realm of photography, rather than mainstream photojournalism and news images.

Analysing cyber images

In 2021, in a bid to understand better the images used to communicate stories about cyber, I began collecting images that accompany news articles and reports, using Google news and image searches of “cyber threats”, “cyber security”, and “cyber warfare” from publications in the UK and US. I then interviewed 15 cyber security experts from Europe, Russia, and the US, inviting them to analyse these images.

In a bid to understand better the images used to communicate stories about cyber, I interviewed 15 cyber security experts from Europe, Russia, and the US, inviting them to analyse cyber images. Esther Kersley

In all the interviews, participants said there was a lack of “good” images to represent cyber. This was an issue they had encountered in their work when needing an image for a conference brochure, a presentation, a book cover, or an article. They were also all in agreement that this is a complex problem to solve as cyber is “intangible”, “diffuse” and “invisible” and recognised that it is a broad topic that refers to many different activities and threats.

Although there was agreement over the issue, there was no consensus on what a “good” or “bad” image was, different experts had radically different perspectives on the images presented to them, and some images prompted strong reactions, both positive and negative. From the analysis and conversations that came from these exercises, I identified three types of images, or three different approaches to representing this topic: “cliched”, “realistic”, and “metaphorical”.

The clichéd, realistic and metaphorical images

The “cliched image”, for example, a man in a hoodie sitting in front of a computer screen (image 1), a padlock, or a human-like robot, are most prevalent in news stories and expert publications. The key problem associated with these images is that they reinforce misrepresentations, stereotypes and inaccuracies. On the hacker image (image 1), one participant said, “It’s like a meme of cyber security that has little to nothing to do with reality”. They went on, “People do carry out cyber-attacks as humans sitting at their laptops, but a lot of cyber security is setting a password, setting up a two-factor identification, the human-machine interface”. It was also seen to be problematic as it reinforces gender stereotypes that cyber is a male domain. This image was also praised for being immediately recognisable: “It does work”, said another participant. “Even if you are not in the cyber security world, the image is ubiquitous.”

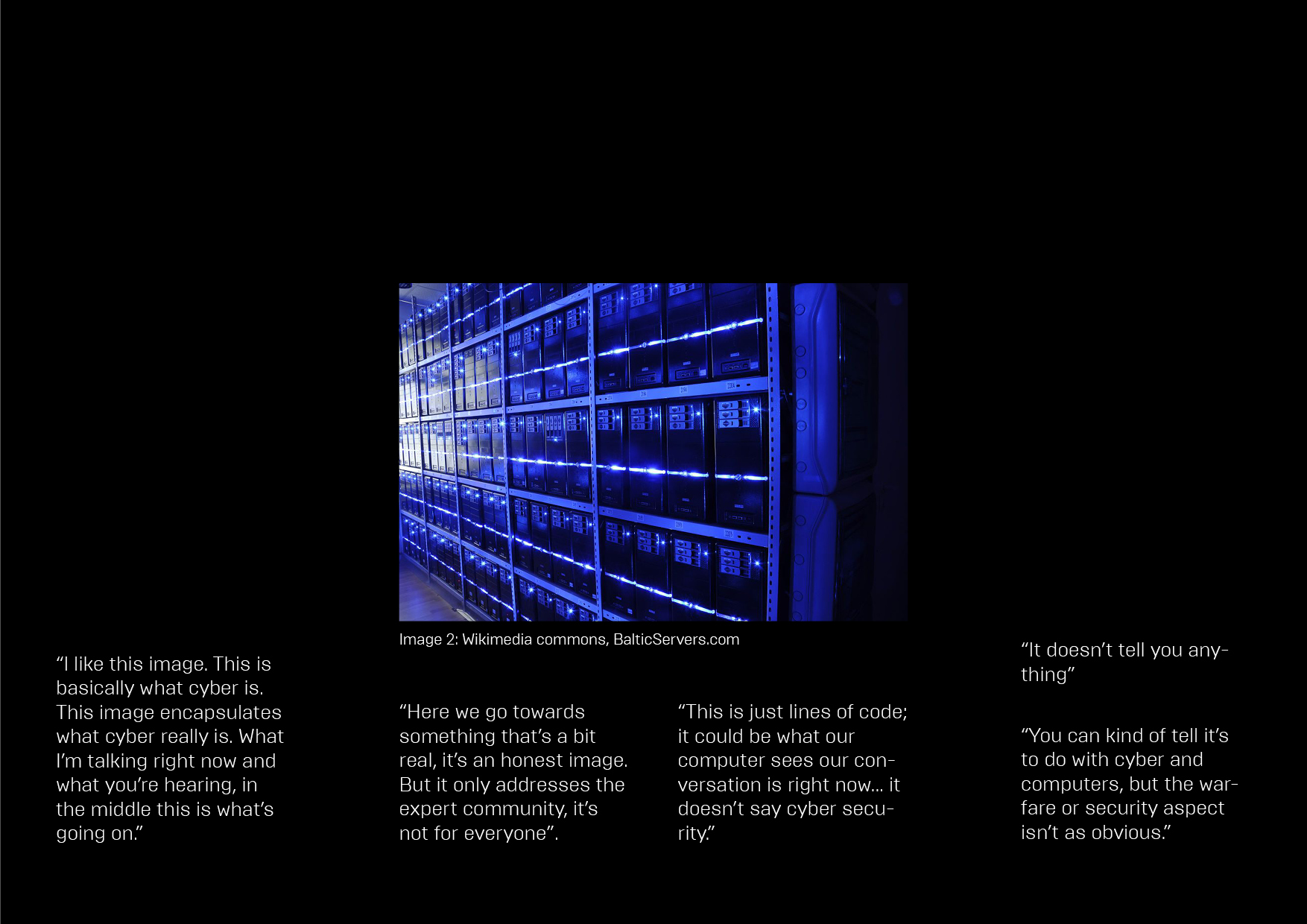

The second type of image identified is the “literal” or “realistic” image, for example showing data centres, military personnel in an operation room, or a computer keyboard. These images were praised as being ‘realistic’ and ‘accurate’: “It shows cyberwarfare addresses physical objects, not just something being done in some fantasy land”, says Dmitry Stefanovich, a research fellow with the Centre for International Security at IMEMO RAS, of the data centre image (image 2). The image of military personnel (image 3) was also praised for being realistic, “It’s not artificial, from a movie or video game” (Elena Chernenko, special correspondent at Kommersant focusing on cybersecurity) and for showing “the human interaction with technology” (Andrew Futter, Professor of International Politics at the University of Leicester). But others criticised them for focusing too heavily on the military when most cyber attacks are conducted by “criminals, young people or hackers”, and a number of interviewees questioned where these images came from and what impact the dominance of US military photos is having on our understanding of cyber.

The final type of image identified are “metaphorical”. These are often illustrations or manipulated images, such as an image showing traditional weapons made out of binary code, or an image of a cityscape with a pixelated bomb exploding. These are most commonly found in magazines, such as The Economist or in newspapers, such as The New York Times. These images were the most polarising amongst participants. On the one hand, they were praised for their storytelling ability and described as ‘clever’, ‘creative’ and ‘interesting’: “Other images don’t affect me or tell me anything. This has a story, a narrative”, says Jason Healey, Senior Research Scholar at Columbia University and Senior Fellow at Cyber Statecraft Initiative at the Atlantic Council. On the other hand, there was also criticism of these images for making too simplistic comparisons or metaphors and potentially trivialising the subject matter. Another participant described one such image as “a mischaracterisation of what cyber attacks are”, and there was concern that these images could play into a kind of mythologisation about technology, “It’s not helpful, it has nothing to do with reality, and you will have a similar attitude to what you read. It contributes to people not taking it seriously,” said Dmitry Stefanovich.

Complexity, the human element, and context

There was a strong desire among all participants to convey complexity and specificity. Most of the interviewees worked in slightly different areas of cyber, and as a result, different images made more or less sense to them depending on the area of their expertise. As Andrew Futter argues in his paper on cyber semantics, in the past decade, the term ‘cyber’ has come to refer to all manner of activities, threats, weapons and even warfare that the word itself has become meaningless. The same issue exists with images: Many of the images attempt to be broad and general, and in doing so, become so diffuse that they too become meaningless. Conversely, images that depict one element of cyber were critiqued for skewing our understanding of what a cyber threat or cyber security is.

Another area of agreement that came out of these interviews was the desire to show the human relationship to this technology and, by extension, its impact. “In most of these images, people are absent,” said Elizabeth Minor, Advisor at Article 36. “These images are talking about technologies, but what we need to be talking about is the people in relation to them”.

'In most of these images, people are absent. These images are talking about technologies, but what we need to be talking about is the people in relation to them', said Elizabeth Minor, Advisor at Article 36. Esther Kersley

Finally, a number of the interviewees commented on the sources of the images I was showing them. Through experience with searching for images themselves, they could identify that some of the images were US military photos and commented on how, as these are readily available online and under a creative commons license, there is an incentive to use them. Dr Katarzyna Kubiak, former senior policy fellow at the ELN and Structured Dialogue Officer at the OSCE, referred to it as “the American colonisation of pictures”. Connected to this, there was discussion about how an institution working on these topics may select an image that reinforces or legitimises their own activities. In other words, there was a desire to unpick the relationship between the image, the subject it is representing, and its broader environment.

Feeding back: Discourse and policy

In 2019, Sean Lawson and Michael K Middleton’s paper on framing cyber security threats explores how language can affect how we see and respond to the world around us. In it, they examine how, for the last 25 years, US cybersecurity discourse has focused on framing cybersecurity using metaphors and analogies to war and the military. This is exemplified by the “Cyber Pearl Harbour” metaphor to describe the risk of a cyber attack against critical infrastructure leading to mass destruction and disruption.

For the last 25 years, US cybersecurity discourse has focused on framing cybersecurity using metaphors and analogies to war and the military. Esther Kersley

Lawson and Middleton argue this has had a real-world impact: The Cyber Pearl Harbour metaphor is not just used by officials in public speeches and picked up by the media but feeds back into the system of internal cyber security discourse and strategising, framing official thinking and planning. The US Strategic Command’s (USSTRATCOM) 2009 “Cyber Warfare Lexicon” , for example, not only recognised the critical importance of language and analogy for understanding cyber threats but also for then developing and carrying out a cyber strategy.

According to Lawson and Middleton, depictions of cyber doom scenarios could lead to “a sense of fatalism and demotivation to act”, which could impair efforts to motivate appropriate policy responses to genuine security threats. They also found that it could distract from real threats, both cyber and non-cyber. After the 2016 Russian interference in the US presidential elections, for example, many observers argued that the focus on Cyber Pearl Harbour had impaired policymakers’ ability to imagine the full range of threats and respond appropriately to cyber threats when they happen. The Russian attack was a campaign of information warfare carried out by social media manipulation, rather than a “Pearl Harbour attack” on critical infrastructure leading to large-scale destruction or fatality.

Deciphering cyber images

Like with the cyber lexicon, cyber images rely on certain tropes. And, like language, images impact how we think about cyber security threats and how we respond to them. Making something visual – especially something that is characteristically hard to envision – is not neutral, nor is it automatically a positive thing, it can have far-reaching consequences that need to be carefully considered.

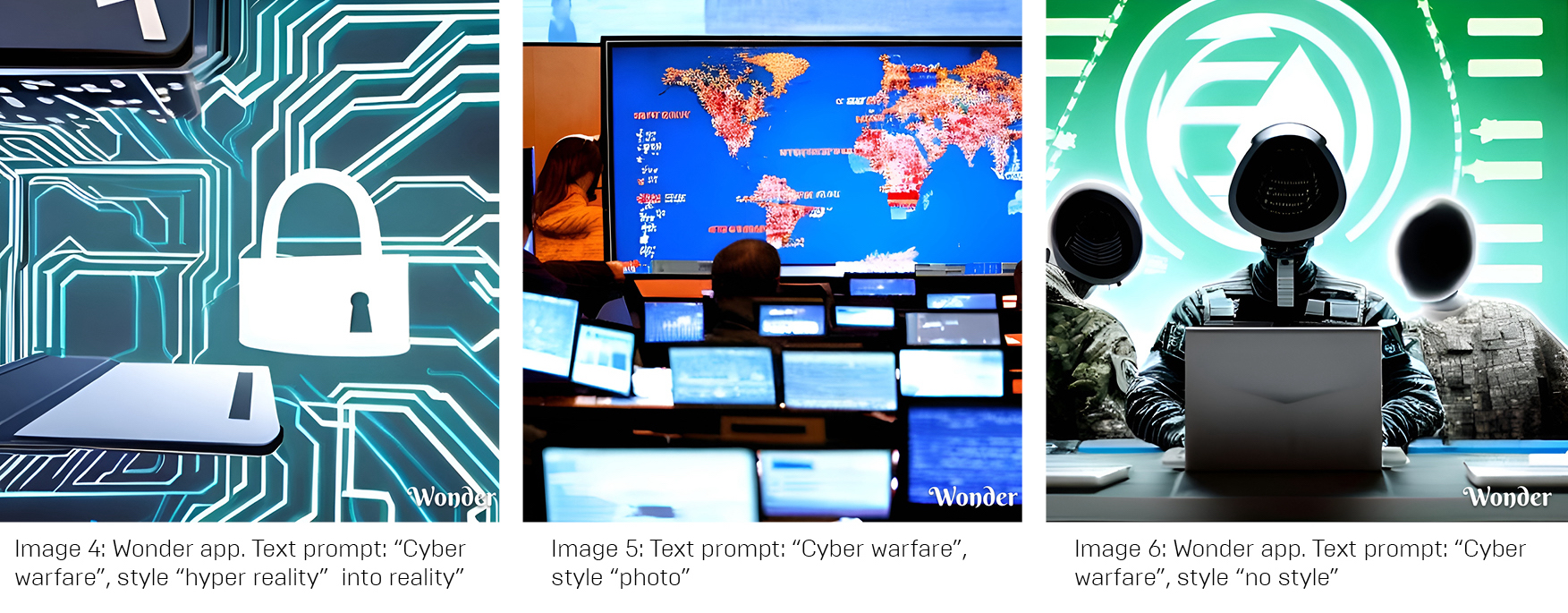

Early in my interviews, I asked participants what image popped into their head when they heard the word ‘cyber’. These were cyber security experts, but all of them described some version of the ‘cliched’ image: rows of 1’s and 0’s, a hooded man in front of a computer, a padlock. In short, it was a reflection of the images they always see. This is a testament to the power of images and the subtle ways they work in our lives. Unsurprisingly, this is mirrored by AI-generated images when given cyber as a prompt (images 4-6 below, generated by prompts from the author in December 2022) – we are fed back the same images we’re used to seeing. To change how cyber and other new technologies are visualised, research into cyber images should be scaled up and diversified to include not just policy experts, but image makers, communications specialists, industry professionals, and the wider public. For this to happen, images need to be recognised as important as language for shaping our understanding of, and response to, new technologies.

The author wishes to thank Lewis Bush and Dr Katarzyna Kubiak for their advice and support, and to the interviewees who generously gave their time.

The opinions articulated above represent the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Leadership Network or all of its members. The ELN’s aim is to encourage debates that will help develop Europe’s capacity to address the pressing foreign, defence, and security policy challenges of our time.

Cover image: Clockwise from left to right: Image 1, Flickr, Christoph Scholz, Image 2, Pixaby, Image 3, PICSHADOW8672, Pixahive, Image 4, Flickr, Richard Patterson, Image 5, Pixaby, Image 6, Wikimedia Commons, David Whelan