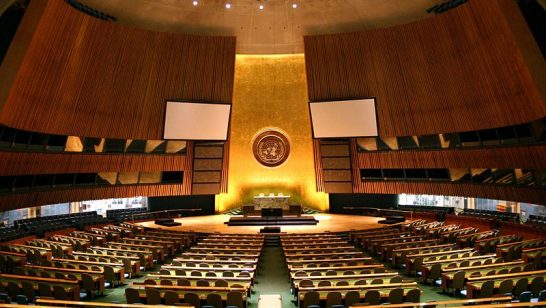

Had it not been for the coronavirus crisis, the world’s diplomats would be now in full swing in the corridors of the UN Headquarters in New York at the 2020 NPT Review Conference. In addition to all the usual (rather gloomy) business, the conference was also meant to commemorate the 50 years of NPT’s coming into force and 25 years since its indefinite extension.

While the indefinite extension is often raised by observers mainly due to the failure of states to deliver on all of the commitments made 25 years ago, there is something very hopeful in the story of the extension. That hopeful element allows the contemporary diplomats to think about ways to avoid the next Review Conference – whenever it may be – resembling a train hitting a wall.

Earlier this year, Wilson Center published a report based on the critical oral history conference of the indefinite extension (which I coedited jointly with Leopoldo Nuti). A major conclusion from this report is that the indefinite extension of the NPT in 1995 was not at all a foregone conclusion. As late as at the fourth Preparatory Committee meeting in three months earlier, relevant actors such as South Africa were floating proposals opposed to the indefinite extension. European diplomats were sceptical about the possibility to gather the sufficient number of votes; and even if they were to be collected, there was no accepted rule about how a vote should take place.

Before the conference, the Western countries were almost totally focused on lobbying tactics and did not discuss what trade-offs could be required. This does not mean that there were no ideas about what concessions could be offered; but that no such ideas were ‘pre-negotiated’. As recalled by the former Dutch Ambassador Jaap Ramaker, in the run-up to the conference, discussion of any ‘meat on the table’ in exchange for the indefinite extension was verboten. Reading archival documents related to the exchanges between US leaders and other world leaders, one can see that the furthest commitments made were to organise future Review Conferences. In a way, diplomats arrived in New York with little idea about how the final result would look like.

The three decisions which were adopted at the end of the conference – on the extension, on principles and objectives for nuclear disarmament, and on strengthening the review process – were all negotiated and agreed in New York. The resolution on the Middle East, which was also adopted by the conference as a consolation prize in exchange for Egypt’s acquiescence to the extension without a vote, was negotiated largely bilaterally between the United States and Egypt.

Cooperation with a leading non-aligned country, such as South Africa, allowed the proponents of the indefinite extension to craft a platform for bridge-building while at the same time split the opposition. While South Africa came up with the first draft of the document which became the Decision on Principles and Objectives, the adoption of this document was according to internal South African documents not a precondition for South African support for the indefinite extension. But these ideas allowed bringing other actors on board, South Africans brought the meat to the table. Countries seeking success in 2020 should, therefore, look for friends (potentially new and across the aisle), who can bring new ideas and moral clout. This is not a small feat – after 1995, ‘reaching across the aisle’ has been a rare feat within the NPT.

‘Vocal radicals’ (as German diplomatic documents called them) were sidelined or divided for the sake of conference success. This further highlights what Heather Williams recently argued– vocal shaming has a proven track record of failure within the NPT setting. As much as disarmament activism is morally appealing, it brings little potential for advancing substantive policy. In 1995, these countries were marginalised and isolated – the most successful one of them, Egypt, managed to extract concessions, but only because it had a significant regional following. Those seeking to avoid a train crash in 2020 may want to consider whether ignoring the vocal spoilers might actually help.

Lastly, the conference president in 1995, Jayantha Dhanapala, engaged in some seriously creative legal drafting and interpretation of the black-letter rules. This remains a lesson for the future Conference Presidents – they are not prisoners of the state parties, but have a large opportunity to shape the outcome. Dhanapala’s strength was not in pushing forward his preferred option (while he never pronounced himself on the issue, rumour has it that he was initially opposed to the indefinite extension); but in identifying a path which can be taken to make a conference a success. The Chair has an opportunity to be a vehicle, and might want to avoid being a roadblock.

The fact that the three preparatory conferences ahead of the 2020 NPT Review Conference were less than stellar is in itself not a problem. If the lessons of 1995 are of any help, it is that the creative diplomacy in New York can actually overcome many of the old divisions. In 2020, this means that as long as diplomats in New York look for constructive partners across the aisle to build coalitions, the conference is not destined for failure. As the Review Conference itself is postponed provisionally until January, the additional time gives state parties an opportunity to seek new partners and allies, and to exchange ideas about new initiatives. Such initiatives may, as in 1995, lead to finding forward-looking documents at the conference. That, of course, requires engaging more in dialogue and less in posturing. However, if states are serious about avoiding a disaster whenever the 2020 NPT RevCon happens, it might be a good starting point.

The opinions articulated above represent the views of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Leadership Network or any of its members. The ELN’s aim is to encourage debates that will help develop Europe’s capacity to address the pressing foreign, defence, and security policy challenges of our time.

Image: Wikimedia Commons, Firestorm cloud over Hiroshima