Article VIII(3) of the Nuclear Weapon Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) requires States Parties to review the Treaty’s implementation and assess if implementation is satisfactory. The Review Process – centred on periodic meetings of the Treaty’s parties – aims to determine whether the Treaty is functioning as expected. Despite this, a majority of NPT non-nuclear-weapon parties (or NNWS) argue that nuclear-weapon states’ (NWS) fulfilment of their obligations remains inadequate.

Throughout the Treaty-mandated Review Conferences (RevCons) held in 1995, 2000, and 2010, significant disarmament commitments were reached, including the decision on “Principles and Objectives for Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Nuclear Disarmament,” the 13 “practical steps,” and the 64-item Action Plan, respectively. However, their implementation has faced significant challenges, with many of their provisions remaining far from realised. In response, the vast majority of NPT States Parties have mobilised to break an entrenched deadlock on the platform of nuclear disarmament.

Humanitarian Initiative: Playing by different rules

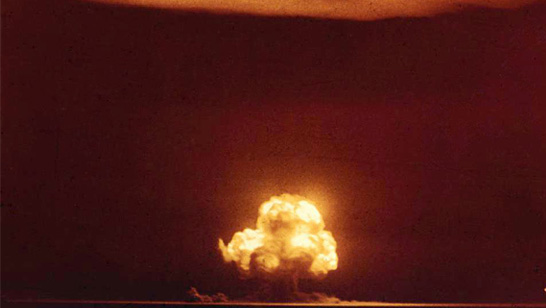

Based on the Humanitarian Initiative – a group of states driven by the idea of accelerating nuclear disarmament due to the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons (hereafter referred to as “ban supporters”) – turned to the UN General Assembly (UNGA) First Committee for initiating negotiations that fell short of reaching consensus within the NPT forum.

Through a UNGA-mandated process, ban supporters managed to establish an open-ended working group (OEWG), follow its recommendation for a negotiating body (United Nations Conference to Negotiate a Legally Binding Instrument to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons), and adopt the treaty text that this body produced (Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons – TPNW). The TPNW was eventually adopted by the clear majority of UN Member States.

Learning from the UNGA

The Humanitarian Initiative’s triumphant journey has shed light on the operational methods and practices of the NPT Review Process, necessitating either essential reforms or filling in gaps externally:

Consensus rule and outcome document

The shift of advocates for humanitarian disarmament to the UNGA reflects a well-established and enduring pattern of circumvention.

In 2013, a similar group of states leveraged their majority in the UNGA to achieve the adoption of the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), which established common standards for the international transfer of conventional weapons. This achievement followed two consensus-based UN conferences that failed to reach an agreement. The ATT proponents shared a common perspective that prioritised human security over the traditional state-centred security approach. These states were able to secure provisions that forbade the export of conventional weapons in violation of arms embargoes or for use in acts of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, or terrorism.

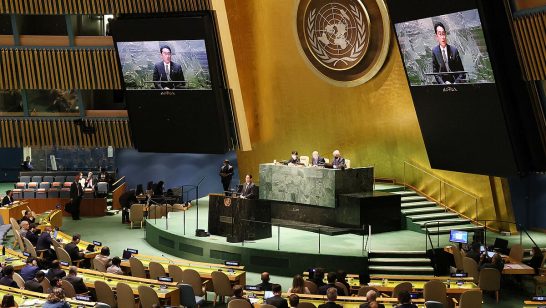

The UNGA stands out due to its non-consensus decision-making process – it allows for adopting resolutions by a majority vote. Konstantin Larionov

As evident, the UNGA stands out due to its non-consensus decision-making process – it allows for adopting resolutions by a majority vote. This differs from the practices followed in the Conference on Disarmament and the NPT meetings.

Established in 1975, the NPT rules of procedure “call for every effort to be made to reach agreement on substantive matters by means of consensus.” This means that decisions are typically reached through consensus, even though the possibility of resorting to voting formally exists.

However, lacking alternative decision rules, such as the “unanimity minus one” model, numerous RevCons have failed to adopt a consensus final document or substantive decisions due to the opposition of either a single State Party or a minority group of delegations.

The NPT’s reliance on consensus tradition is further complicated by its practice of producing an all-encompassing final document meant to reflect every discussed issue: if a State Party objects to a single wording, it halts progress on the entire text.

Unless the NPT opts to reconfigure the report’s structure – for example, by reflecting individual recommendations and proposals that have garnered consensus support or segmenting the report into distinct sections – the most advantageous format continues to mirror that employed in the UNGA. This approach ensures an equitable opportunity for resolutions to succeed through voting and diminishes the likelihood of proposed wordings being diluted or entirely left out.

Addressing the evolving nature of security risks through a coordinated response

Throughout the UNGA First Committee negotiating process, ban supporters achieved formal recognition for the moral position that the use of nuclear weapons is incompatible with concepts of humanity, as well as the norm to stigmatise nuclear weapons and a nuclear deterrence-based notion of security.

While the International Court of Justice (ICJ) did not definitively determine the legality of the threat or use of nuclear weapons for defensive purposes, the Humanitarian Initiative has further solidified the customary rejection of such actions. The ELN’s Protecting the Non-Proliferation Treaty project has also suggested that the UNGA could seek a new Advisory Opinion from the ICJ on the legality of nuclear threats, considering post-1996 developments.

Presently, these reverberations extend beyond the General Assembly, evident in the G20 leaders’ declaration from last year that unequivocally condemned the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons as “inadmissible.”

Within the UN system, these norms now have the potential to extend to discussions on various doctrinal measures, including refraining from first use or eliminating launch-on-warning policies.

Regrettably, these crucial intersections are rarely addressed within the NPT Review Process platform, resulting in nuclear disarmament commitments existing in isolation from other pressing global issues. Given the UNGA’s broad political mandate and capacity to rally a much broader range of coordinated efforts across the UN system, utilising its wealth of expertise in these specific areas could hold the promise of becoming focal points for General Assembly resolutions. This, in turn, could open pathways for potential new multilateral agreements.

While there is no assurance that these agreements will definitively bring about change among nuclear-armed states, the General Assembly’s authority, as the most inclusive body in the UN, can shed light on critical issues and exert pressure on those responsible for problematic actions.

Institutional capacity and responsiveness

By convening annually, the UNGA exhibits greater responsiveness to immediate challenges and maintains more frequent activity than the NPT community. In contrast, RevCons occur once every five years and lack a continuous institutional presence.

Currently, preparatory committees find themselves unable to bridge this void between RevCons. As Paul Meyer rightly pointed out, the annual PrepCom meetings “have been content with taking a few, basic procedural steps and have put off any decisions on substance to the review conferences themselves.”

Even worse, due to the disagreement on the documents to be included in the latest PrepCom’s procedural report, the reflections (or recommendations, as presented by the Chair), whether related to procedural or substantive aspects, were not formally endorsed for consideration in the next 2024 PrepCom session. This development deals a significant blow to the principles of “coordination” and “continuity” crucial for ensuring the effective consolidation of all agreed proposals into final recommendations for the 2026 NPT RevCon.

The UNGA remains the only platform capable of swiftly laying the groundwork for broader legal frameworks in non-proliferation and disarmament-related matters. Konstantin Larionov

Without annual NPT meetings authorised to adopt substantive decisions or a mechanism for arranging early emergency meetings, the UNGA remains the only platform capable of swiftly laying the groundwork for broader legal frameworks in non-proliferation and disarmament-related matters. Moreover, it holds sufficient authority to address immediate threats of non-compliance in situations where the UN Security Council (UNSC) has not intervened or has proven ineffective. Unlike the UNSC, which is endowed with enforcement powers, General Assembly resolutions can act preventively by urging a country to restore compliance. This way, North Korea’s violation of its IAEA Safeguards Agreement and its NPT obligations established a precedent for the UNGA’s involvement. Additionally, the 2022 landmark resolution now empowers the UNGA to hold the five permanent UNSC members accountable for their use of the veto.

For a considerable period, efforts to address institutional gaps within the NPT through proposals for a standing bureau or a support unit have not been included in the final document. The NPT working group on Strengthening the Review Process, established after the 2022 NPT RevCon to readjust the review cycle, failed to adopt draft recommendations despite several promising proposals.

In this context, an alternative method for restructuring the procedural development of the NPT could be to bolster accountability through the UNGA institutional apparatus. Although the NPT calls for regular reporting from States Parties, it is deficient in the oversight capacity needed to receive, process and formulate responses to these reports. Yet, the transition of this responsibility to the UNGA’s jurisdiction is likely to face resistance, particularly from nuclear-weapon States Parties who may be hesitant about ceding control over the Review Process.

Implications for the NPT

Much like the credibility crisis that affected the Humanitarian Initiative over disarmament commitments, dissatisfaction has been steadily increasing among Arab states due to the insufficient progress in implementing the 1995 Middle East resolution. While the NPT Review Process played a significant role in initiating discussions on a WMDFZ in the Middle East, the indefinite postponement of the 2012 conference and the failure of the 2015 NPT RevCon to adopt a final document have fueled the coalition’s determination to press for progress outside the NPT framework. Ultimately, under the League of Arab States’ project, the UNGA passed a resolution on 22 December 2018 to convene a Conference with the aim of launching on its own terms the negotiation process for a legally binding WMDFZ in the Middle East agreement.

The effectiveness of addressing demands for a legally binding instrument to prohibit nuclear weapons and a WMDFZ in the Middle East within the UNGA-mandated process became apparent when it helped alleviate some of the pressure typically associated with these issues during the NPT meetings. Konstantin Larionov

The effectiveness of addressing demands for a legally binding instrument to prohibit nuclear weapons and a WMDFZ in the Middle East within the UNGA-mandated process became apparent when it helped alleviate some of the pressure typically associated with these issues during the NPT meetings. During the 2022 NPT RevCon, both ban supporters and Arab states demonstrated an encouraging willingness to compromise to preserve the integrity of the Treaty, even though the draft final document was significantly weakened on all three pillars.

Contrary to some apprehensions, this shift has not caused a separation between the States Parties to the NPT into those “inside” and “outside” the Review Process. Both the Humanitarian Initiative and the League of Arab States made deliberate efforts to ensure that progress achieved outside the NPT was duly recognised by the 2022 NPT RevCon.

A more pessimistic view suggests that due to the persistently unfavourable environment within the NPT Review Process towards the disarmament provisions promoted by the Humanitarian Initiative, backed by various Non-Aligned States Parties and the New Agenda Coalition, the expected transition of the “critical mass” of NNWS (ban supporters account for an unprecedented 83% of the NPT States Parties) towards the UNGA may pose risks to the legitimacy of the NPT platform.

While the prospect of a mass exodus of States Parties from the Treaty under Article X is improbable, the NNWS might show reduced interest in engaging in discussions within the NPT. Eventually, this might evolve into a “Who can RSVP last?” contest, where States Parties hurriedly assemble smaller national delegations comprising diplomats in less senior positions. In the grand scheme of things, this might result in diminished institutional memory among political leaders and diplomatic officials of the NPT Review Process and its major achievements, encompassing those endorsed in 1995, 2000, and 2010.

Key issues to address in the UNGA

The NPT’s attractiveness to states and its image as the cornerstone of the global non-proliferation regime will fade unless there are concerted efforts to bridge the divide between promises and actual implementation. Repeated after each unsuccessful Conference, it may sound like a cliché, but the next few years of the review cycle leading to the 2026 NPT RevCon will prove pivotal in determining whether the Review Process remains stable or succumbs to significant challenges.

The NPT's attractiveness to states and its image as the cornerstone of the global non-proliferation regime will fade unless there are concerted efforts to bridge the divide between promises and actual implementation. Konstantin Larionov

The General Assembly can serve as a UN channel to mitigate discrepancies within the NPT, without undermining its widely recognised reputation. This approach would aid in developing modalities and formulating policy recommendations for crucial non-proliferation and disarmament commitments, which had been hindered for decades within the NPT:

- Should the NPT States Parties not succeed in advancing the step-by-step disarmament process, such as establishing subsidiary bodies under the NPT to address longstanding agreed objectives of the Treaty (e.g., negotiating a Fissile Material Cut-Off Treaty – FMCT), these states might also choose to discuss the modalities of fissile material production ban negotiations in the UNGA First Committee. The UNGA could then adopt a resolution to authorise these negotiations under its auspices.

- In relation to the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), one potential approach is to consider the implementation of provisional application as a means to circumvent the requirements of Article XIV and Annex 2 temporarily. Taking such action could significantly mitigate the present risks posed by a small group of states obstructing the CTBT’s entry into force.

In practice, a special conference involving ratified CTBT states and signatory states (as observers) could help with negotiating a protocol on provisional application. It could subsequently secure endorsement through a majority vote in the UNGA.

It is unlikely that the General Assembly’s endorsement will force the remaining eight States listed in the CTBT’s Annex 2 to ratify the treaty. However, reinforcing the legal validity of the norm against nuclear testing would accelerate, rather than diminish, the motivations for reluctant states to do so.

This is evident from the cases of Argentina and Brazil, which had advanced nuclear programs but were not initially part of the Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone in Latin America and the Caribbean, established by the Treaty of Tlatelolco. Over time, the norm against nuclear weapons prompted these two states to dismantle their nuclear capabilities and join the treaty.

Otherwise, if the long-standing agreed goals, such as FMCT and the CTBT, continue to be merely ritualistic calls without substantial action, the commitment of States Parties to these goals may wane.

- Calls for the reduction of nuclear forces and reliance on nuclear weapons in security doctrines are also at risk of losing much of their relevance as the comprehensive TPNW process for the total elimination of nuclear weapons gains traction.

Initially, the draft final document of the 2022 NPT RevCon prominently featured a number of nuclear risk reduction measures. However, as the delegation of Russia blocked approval for the final document, the proposed language on risk reduction did not receive formal recognition.

If these proposals are not implemented as a result of the eleventh review cycle, the view that risk reduction distracts from and is not conducive to the ultimate goal of nuclear disarmament is likely to gain more sympathy from non-nuclear-weapon States Parties.

At the same time, shifting these matters to the UN forum would address criticisms that risk reduction talks excessively occupy the Review Conference’s time. An essential first step in this process is establishing a Group of Governmental Experts, which can be appointed by the Secretary-General following the General Assembly endorsement, alongside an OEWG capable of negotiating specific documents or, at the very least, facilitating open discussions among Member States. Negotiations with a similar scope are underway within the P5 framework. Still, they lack inclusivity as they only involve the five States – officially recognised as possessing nuclear weapons by the NPT, and are conducted at an expert rather than a ministerial level.

The NPT plays an unassailable role as the symbol of international efforts to curb nuclear proliferation. At the same time, it stands as just one element among a larger set of arrangements that together form the global non-proliferation regime. Why close the old door and open a new one when you have the option to forge a corridor that connects the best of both worlds?

The opinions articulated above represent the views of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Leadership Network or any of its members. The ELN’s aim is to encourage debates that will help develop Europe’s capacity to address the pressing foreign, defence, and security policy challenges of our time.

Image: UN General Assembly. Wikimedia Commons, Pine