States parties to the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) met in Vienna last summer for the Preparatory Committee (PrepCom) to the 2026 NPT Review Conference (RevCon). In advance, member states were invited to a Working Group on strengthening the review process. These first three weeks of meetings in this 11th NPT review cycle ended with the working group not adopting joint recommendations and some state parties (namely Iran, Russia, and China) blocking the PrepCom chair’s efforts to issue the official summary of the meeting as a working paper. In the absence of consensus documents, the pressure on this review cycle to produce tangible results is as urgent as ever. Preventing nuclear use and threat of use, which is in all NPT states’ interests, should be the first priority of the 11th NPT Review Cycle.

As a key issue, NPT states should discuss whether it is possible to objectively distinguish between varieties of ‘nuclear threats’, including whether a legitimate distinction between ‘offensive’ and ‘defensive’ nuclear threats exists. Such an effort could help bridge the gap between states condemning any and all nuclear threats under any circumstances and those states that stand firmly behind ‘defensive’ nuclear threats. At the 2022 RevCon, NPT member states, for the first time in the treaty’s history, condemned specific nuclear threats made by an NPT member state.[1] Yet the conference failed to adopt language and develop a common understanding of “nuclear threats” more broadly. Many states, at both the RevCon and the PrepCom, echoed the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) meeting of states parties’ June 2022 condemnation of “any and all nuclear threats, whether they be explicit or implicit and irrespective of the circumstances.” At PrepCom, some states, including Norway, Japan, and Austria, welcomed the G20 Bali Statement that “[t]he use or threat of use of nuclear weapons is inadmissible”. However, for the most part, discussions focussed on the implicit and explicit threats of nuclear weapons use by Russia in the context of its war of aggression against Ukraine. At the 2023 PrepCom, France, joined by 73 other states, also expressed concern about DPRK’s “continued irresponsible and destabili[s]ing nuclear rhetoric in which it declares its pursuit for tactical nuclear weapons and claims it might use its nuclear weapons pre-emptively” – indicating a rhetorical shift on how France perceives nuclear threats, widening the focus of discussions.

Despite the increased attention on nuclear risks, disagreement persists amongst state parties over what should and should not be considered a nuclear threat. As practices of nuclear sharing came under question, Nuclear Weapon States (NWS) and their allies condemned only certain nuclear threats and argued that some nuclear threats are ‘acceptable’.

NNWS’ critique of the practice of nuclear deterrence has seldom been more strident in the NPT context than at the 2023 PrepCom, and the responses from some NWS have equally reached unusual fever pitches, with states on both sides of the debate implying that the taboo against nuclear use does not exist or is not credible.

The NPT may be more at risk than ever of being ruptured by two incompatible worldviews, including two rival conceptions of ‘nuclear threats’: NWS and allies view implicit nuclear threats as part of nuclear deterrence as legitimate, while many NNWS condemn even the threats to use nuclear weapons inherent to the practice of nuclear deterrence.

The NPT may be more at risk than ever of being ruptured by two incompatible worldviews, including two rival conceptions of 'nuclear threats'. Ananya Agustin Malhotra and Maren Vieluf

At the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW)’s Meetings of States Parties, for example, TPNW states parties condemned “any and all nuclear threats, whether they be explicit or implicit and irrespective of the circumstances.” Taking a strong stand against any possible “responsible” nuclear threats at the Second Meeting of States Parties in December 2023, TPNW states parties labelled nuclear deterrence itself “the threat of inflicting mass destruction”, which “runs counter to the legitimate security interests of humanity as a whole.” In no uncertain terms, they declared that even implicit nuclear threats constitute a “dangerous, misguided and unacceptable approach to security. Nuclear threats should not be tolerated.” While welcoming the G20 statement on the inadmissibility of nuclear threats, they firmly stated that such statements must be backed up by meaningful action.

To reiterate the taboo against nuclear use and threat, NPT member states should endeavour to find a common understanding of a ‘nuclear threat’ amongst all NPT member states. This could build on the ICJ’s existing definition per its 1996 Advisory Opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons – “a signalled intention to use force if certain events occur” – and offer a consensus on whether it is possible to objectively distinguish between varieties of ‘nuclear threats.’

Calling out nuclear threats

At the 2023 PrepCom, several states, led by Austria and the New Agenda Coalition condemned all nuclear threats, including implicit threats inherent to the practice of nuclear deterrence. Emphasising that the humanitarian consequences and existential risks render both the use and threat of use of nuclear weapons incompatible with international humanitarian law, these states argued for a paradigm shift away from deterrence and towards nuclear disarmament. They held that indefinite possession of nuclear weapons is indefensible, and the only way to eliminate risks associated with nuclear weapons is through the total elimination of nuclear weapons.

For Austria, nuclear deterrence “relies on the credible threat of the actual use of nuclear weapons.” So long as some states rely on nuclear deterrence, argued Ambassador Alexander Kmentt, “there cannot be a real or credible taboo against the use of nuclear weapons, because nuclear deterrence is […] based on concrete plans and the intention of using these weapons of mass destruction and inflicting unthinkable suffering with potentially catastrophic global consequences.”

These NNWS warned that so long as some states continue to possess nuclear weapons and justify the value of nuclear deterrence or the need for extended nuclear security guarantees, citing security reasons for doing so, others may aspire to acquire them. In turn, more states will seek to rely on nuclear deterrence in their respective security policies, counteracting nuclear non-proliferation efforts. But these states’ views are juxtaposed by those of the NWS and their allies, who justify certain nuclear threats made in the context of deterrence as permissible.

Justifications of (certain) nuclear threats

As we argued in a recent ELN policy brief on the inadmissibility of nuclear threats, there is an intimate relationship between the practice of nuclear deterrence and the condemnation of (certain) nuclear threats. NWS and their allies continue to act as custodians of the nuclear status quo, stating that the security environment does not (yet) allow for nuclear disarmament and categorising their nuclear weapons policies and doctrines as responsible and defensive, and therefore acceptable.

The NWS continuously refer to their engagement concerning risk reduction, transparency, and, to varying degrees, the Fissile Material Cut-Off Treaty (FMCT) and the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT). At the 2023 PrepCom, the United States also expressed commitment to identify “political and technical challenges to nuclear disarmament and work to overcome them” without specifying any such efforts. Each of the P5 states denounced what they saw as irresponsible or reckless behaviour and rhetoric by their geopolitical rivals while emphasising the solely defensive nature of their respective nuclear weapons policies. For example, China criticised the United States’ new agreements with the Republic of Korea and the AUKUS deal as “a typical act of double standards” which will “open the Pandora’s box of nuclear proliferation”, while the United States denounced Russia’s war against Ukraine and “irresponsible nuclear rhetoric” as a bludgeon to the “system of nuclear restraint” upon which the NPT rests.

China and the U.S. can agree on one thing: their own nuclear posture is defensive and responsible, but their rival’s nuclear postures are offensive and coercive in nature. China stated that while its nuclear weapons arsenal solely serves the purpose of “deterring nuclear war”, others use them to “intimidate”, “bully”, and “seek […] hegemony.” China also proposed that the NWS should work to “conclude a treaty on the mutual no-first-use of nuclear weapons, and not target their nuclear weapons at any country.” Such a treaty, however, is unlikely to gain traction in the other P5. The US, for example, cites allies’ concerns that a policy would undermine the effect of deterrence.

In a promising development, some NWS reaffirmed existing negative security assurances against non-nuclear weapon states. The United Kingdom, China, and Russia indicated their willingness to sign additional existing protocols, particularly the Treaty on the Southeast Asian Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone, which none of the NWS have signed to date. All NWS should build on this progress by clarifying what they have committed to when they promise not to use — or threaten to use — nuclear weapons against NNWS.

Yet, at other times, NWS appeared to backslide from commitments against making nuclear threats. France and the United Kingdom contested a line in the Chair’s Draft Factual Summary, which characterised the January 3, 2022 statement by the P5 that a “nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought” as ‘affirming the norm against the use of nuclear weapons.’ They argued that the joint statement was never meant to indicate that there is a norm against the use of nuclear weapons, implying that no such norm exists. Poland, a U.S. ally, responded to critiques of nuclear deterrence by arguing that nuclear deterrence was essential to uphold states’ security, which ought not to be diminished in the pursuit of the goals of the NPT, including its third pillar of disarmament–a clear contradiction, as perpetual nuclear deterrence is ultimately incompatible with NPT states’ obligations to “pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating…to nuclear disarmament.” Russia, which has made the most explicit nuclear threats since its illegal invasion of Ukraine, for its part criticised U.S. nuclear weapons stationed in Europe, stating that this retention “incit[es] compensatory countermeasures.”

Thus, all nuclear weapons states continue to justify nuclear deterrence and implicit nuclear threats, citing the necessity to uphold national security and alliance commitments. But in the long term, failing to reduce the salience of nuclear weapons in security doctrines over time will further entrench the divide between NWS and NNWS and weaken the NPT regime.

Considerations for the 2026 NPT Review Cycle

Finding common ground on what the NPT considers (un-)acceptable nuclear threats will not be easy. Yet, as a first step, to reinforce the nuclear taboo and to address the growing divide between NWS and NNWS, member states should confront whether a perceived need to define and condemn nuclear threats is an urgent task for this review cycle. This dialogue, however, should include NNWS, as the working paper by the New Agenda Coalition highlighted: “[a]ttempts to normalise the threat of use of nuclear weapons, nuclear rhetoric or efforts designed to make nuclear weapons palatable must be challenged or they will continue to damage the Non-Proliferation Treaty regime.” The repetition of the classification of use and threat of use as “inadmissible” with the September 2023 G20 New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration should be seen as an opening to further discussions.

States could unequivocally condemn threats of nuclear use made during an ongoing conventional conflict or those that imply offensive military action. NPT States could call on all NWS to clarify their existing commitments not to threaten NNWS through existing negative security assurances. Additionally, NWS could undertake measures that demonstrate their defence and deterrence strategies reflect only a defensive posture (i.e., de-alerting, de-targeting, No First Use, NSAs). This commitment could then be reflected in NWS’ national reporting and relate to other risk reduction and confidence-building measures.

NPT member states should, therefore, in the 11th review cycle aim to:

- Enhance transparency obligations of NWS regarding their nuclear weapons policies, including current scenarios of and thresholds for nuclear use.

- Advance dialogue and action on Article VI disarmament obligations.

- Defend and strengthen the nuclear taboo in both language and action by reinforcing and expanding other norms enshrined in the NPT, including the norm against explosive nuclear tests.

- Establish a subsidiary body at both within the 2026 RevCon review cycle and the Conference on Disarmament, working towards an unconditional, universal, and legally binding instrument to assure NNWS against the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons.

- Discuss perceptions of the (in-)admissibility of nuclear threats and work towards a common understanding of what NPT state parties consider a nuclear threat and condemn such threats collectively.

[1] This is the case as far as the authors can tell from lexical analysis of 5000 publicly available NPT documents using MaxQDA. Before the 2022 Review Conference, states did not identify concrete nuclear threats and did not reference them as being unjustified. States did state the shared goal “of a world without nuclear threats” and condemned risks associated with rogue states, miscalculations and misinterpretations as well as terrorists, but did not call out a particular state or actor for nuclear threats.

The opinions articulated above do not necessarily reflect the position of the ELN or any of its members. These views are those of the authors in their personal capacities alone, and do not represent the views of any of the institutions with which they are affiliated. The ELN’s aim is to encourage debates that will help develop Europe’s capacity to address the pressing foreign, defence, and security policy challenges of our time.

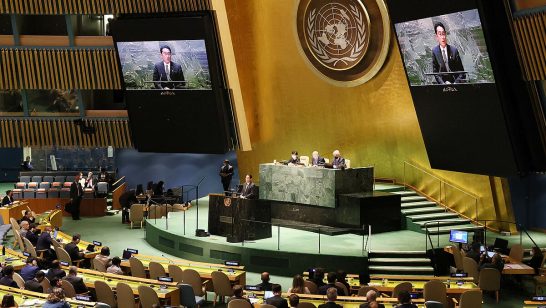

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons / US Department of Defense