This article was originally published in The Korea Times and can be read here.

A worrying divide has been growing between South Korea and its Asia-Pacific security partners. Although Seoul regards the threat posed by North Korea as more acute than ever before, countries including Japan, Australia, the United States and Britain are overwhelmingly preoccupied with China’s regional ambitions. But they ignore Pyongyang’s continuing brinkmanship at their peril. Escalation and proliferation risks are growing on the Korean Peninsula, and Seoul’s mounting sense of isolation exacerbates both dangerously.

A recent project conducted by the Asia-Pacific Leadership Network (APLN) and the European Leadership Network (ELN) explored perceptions of nuclear risk in South Korea, Australia, Japan and Britain. Experts and officials in the four countries were asked a series of questions about the risk of conflict in Northeast Asia. Although there was a fairly broad consensus among them on the main causes for concern in the Taiwan Strait, opinions diverged regarding escalation risks on the Korean Peninsula. For example, whereas South Koreans considered it likely that a Korean conflict will take place in the near future, with devastating consequences for South Korea’s national security, participants from the other three countries downplayed these risks and dismissed South Korean concerns that North Korea might intentionally initiate a crisis.

Escalation and proliferation risks are growing on the Korean Peninsula, and Seoul’s mounting sense of isolation exacerbates both dangerously. Tanya Ogilvie-White

This gap in South Korea’s threat perceptions could have serious security implications over the next few years, especially if Seoul sees self-reliance as its only option for dealing with its hostile and unpredictable neighbour. Escalation dangers are already growing — recently, South Korea’s defence minister instructed the military not to show restraint in response to North Korean provocations. Instead, it has been ordered to “take action immediately, strongly and until the end,” and not wait for permission from their political leaders. This change in military posture has occurred against a backdrop of increasing domestic support for an independent South Korean nuclear weapons capability, spurred on by the North’s constant verbal threats and missile tests, and by concern that Seoul will face an existential crisis if U.S. alliance resolve wanes.

If there is a change of administration after the U.S. elections this year, South Korea’s deep insecurity and sense of isolation could intensify, increasing proliferation, conflict and escalation dynamics. Urgent steps should be taken to reduce these risks, including measures to strengthen bilateral ties between South Korea and its security partners. For while Japan, Australia and Britain have taken great strides in strengthening bilateral ties with one another, they are only just beginning to explore the potential of their respective partnerships with South Korea. These efforts need to be deepened and accelerated.

If there is a change of administration after the U.S. elections this year, South Korea’s deep insecurity and sense of isolation could intensify, increasing proliferation, conflict and escalation dynamics. Tanya Ogilvie-White

The four countries should also engage more closely in policy dialogue and coordination as a group and carefully consider how they would plan to uphold their shared security interests on the Korean Peninsula, including in conditions of conflict and conflict escalation. As they undertake these activities, they should take steps to reassure Pyongyang and Beijing that their coordination efforts are defensive, based on their shared, legitimate security interests and not aimed at creating an Asian NATO.

Two collaborative initiatives should be prioritised:

First, experts in each of the four countries who have deep knowledge of the nuclear non-proliferation regime should be tasked with analysing and communicating the role that such frameworks play in promoting stability in Northeast Asia, and the likely regional and global consequences of allowing the Treaty on the Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) regime to collapse. This is critically important because the joint APLN-ELN project identified a growing dismissiveness among policymakers — especially in Seoul — regarding the value of key multilateral legal and normative frameworks, including the NPT.

Second, officials from the four countries should conduct tabletop exercises to explore specific conflict scenarios on the Korean Peninsula, including under conditions of U.S. retrenchment. These exercises should be used to improve understanding between the three Asia-Pacific countries of escalation risks and their respective approaches to crisis decision-making, and test responses to potential crisis signals from Chinese and North Korean leaders. Britain, as an actor from outside the region, could host these exercises in a neutral location.

The tendency among experts and officials in Australia, Japan, Britain and the U.S. to treat nuclear risks on the Korean Peninsula as secondary to those in the Taiwan Strait is cultivating a sense of resignation among South Koreans that they must ‘go it alone.’ Tanya Ogilvie-White

Policymakers must use these and other initiatives to refocus their attention on North Korea’s nuclear activities and do so in a way that fully engages South Korean experts and officials. The tendency among experts and officials in Australia, Japan, Britain and the U.S. to treat nuclear risks on the Korean Peninsula as secondary to those in the Taiwan Strait is cultivating a sense of resignation among South Koreans that they must ‘go it alone.’ Bringing North Korea back onto the security agenda could reduce proliferation pressures in South Korea and help bolster strategic stability in Northeast Asia.

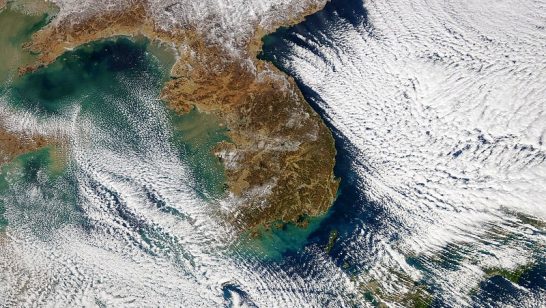

Image credit: Imjingak Park, DMZ, South Korea (Domenico Convertini, Flickr).

The opinions articulated above represent the views of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Leadership Network or any of its members. The ELN’s aim is to encourage debates that will help develop Europe’s capacity to address the pressing foreign, defence, and security policy challenges of our time.